Better in PDF: Prohibition against Fraud

I. Introduction

A. Background

B. Observations in the Credit Default Swap Market

C. Overview of the Proposal

1. Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1

2. Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c)

3. Proposed Rule 10B-1 20

II. Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1: Prohibition Against Fraud, Manipulation, and Deception in Connection With Security-Based Swaps

A. Prior Commission Action

B. Scope of Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1

1. General Antifraud and Anti-Manipulation Provisions

2. “Purchases” and “Sales” in the Context of Security-Based Swaps and Limited Safe Harbor for Certain Limited Actions

3. Prohibition on Price Manipulation

C. Liability Under Proposed Rule 9j-1 in Connection With the Purchase or Sale of a Security

D. Preventing Undue Influence Over Chief Compliance Officers; Policies and Procedures Regarding Compliance With Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1, Proposed Rule 10B-1 and Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c)

E. Request for Comment

III. Proposed Rule 10B-1: Position Reporting of Large Security-Based Swap Positions

A. Proposed Definitions and Thresholds Start Printed Page 6653

1. Reporting Thresholds for Debt Security-Based Swaps (Including CDS)

2. Reporting Threshold for Security-Based Swaps on Equity

3. Amendments to a Previously Filed Schedule 10B

B. Information Required To Be Included in Schedule 10B

C. Cross-Border Issues

D. Structured Data Requirement for Schedule 10B

E. Request for Comment

IV. General Request for Comment

V. Paperwork Reduction Act

A. Summary of Collections of Information

B. Proposed Use of Information

C. Respondents

D. Total Annual Recordkeeping Burden

1. Initial Costs and Burdens

2. Ongoing Costs and Burdens

E. Collection of Information Is Mandatory

F. Confidentiality

G. Request for Comment

VI. Economic Analysis

A. Introduction

B. Broad Economic Considerations

C. Baseline

1. Existing Regulatory Frameworks

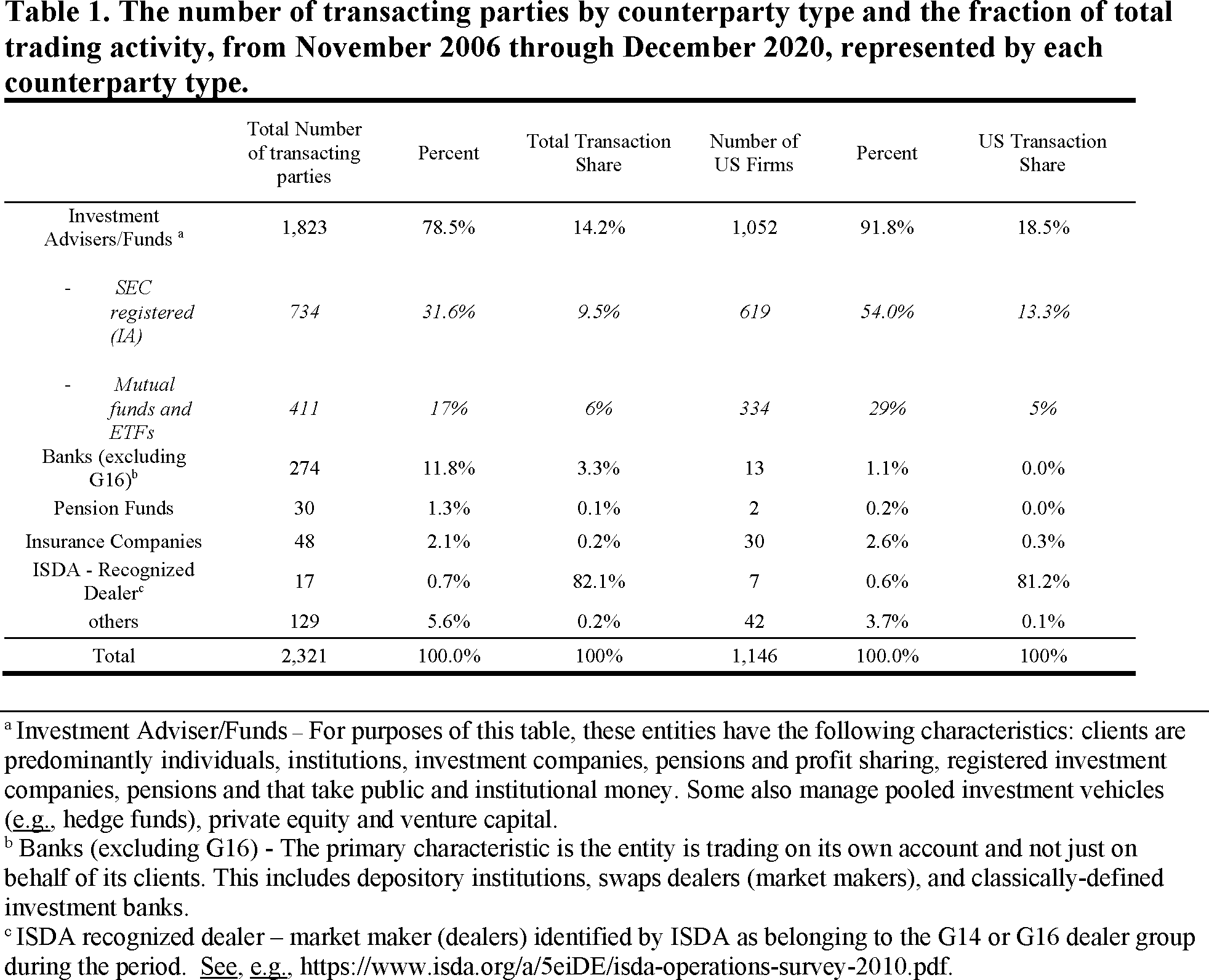

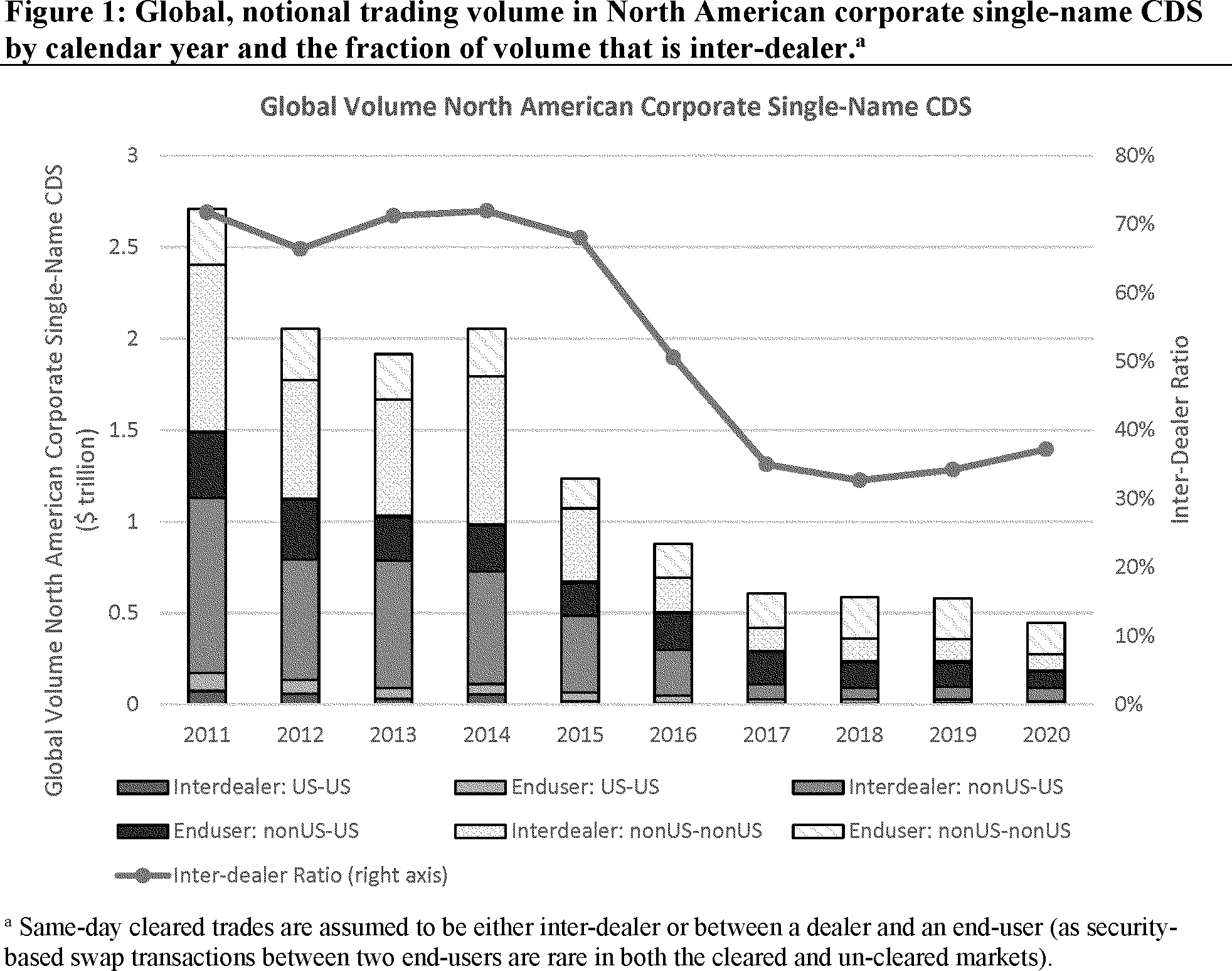

2. Security-Based Swap Data, Market Participants, Dealing Structures, Levels of Security-Based Swap Trading Activity, and Position Concentration

D. Consideration of Costs and Benefits; Consideration of Burden on Competition and Promotion of Efficiency, Competition and Capital Formation

1. Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1 and Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c)

i. Benefits

ii. Costs

2. Proposed Rule 10B-1

i. Benefits

ii. Costs

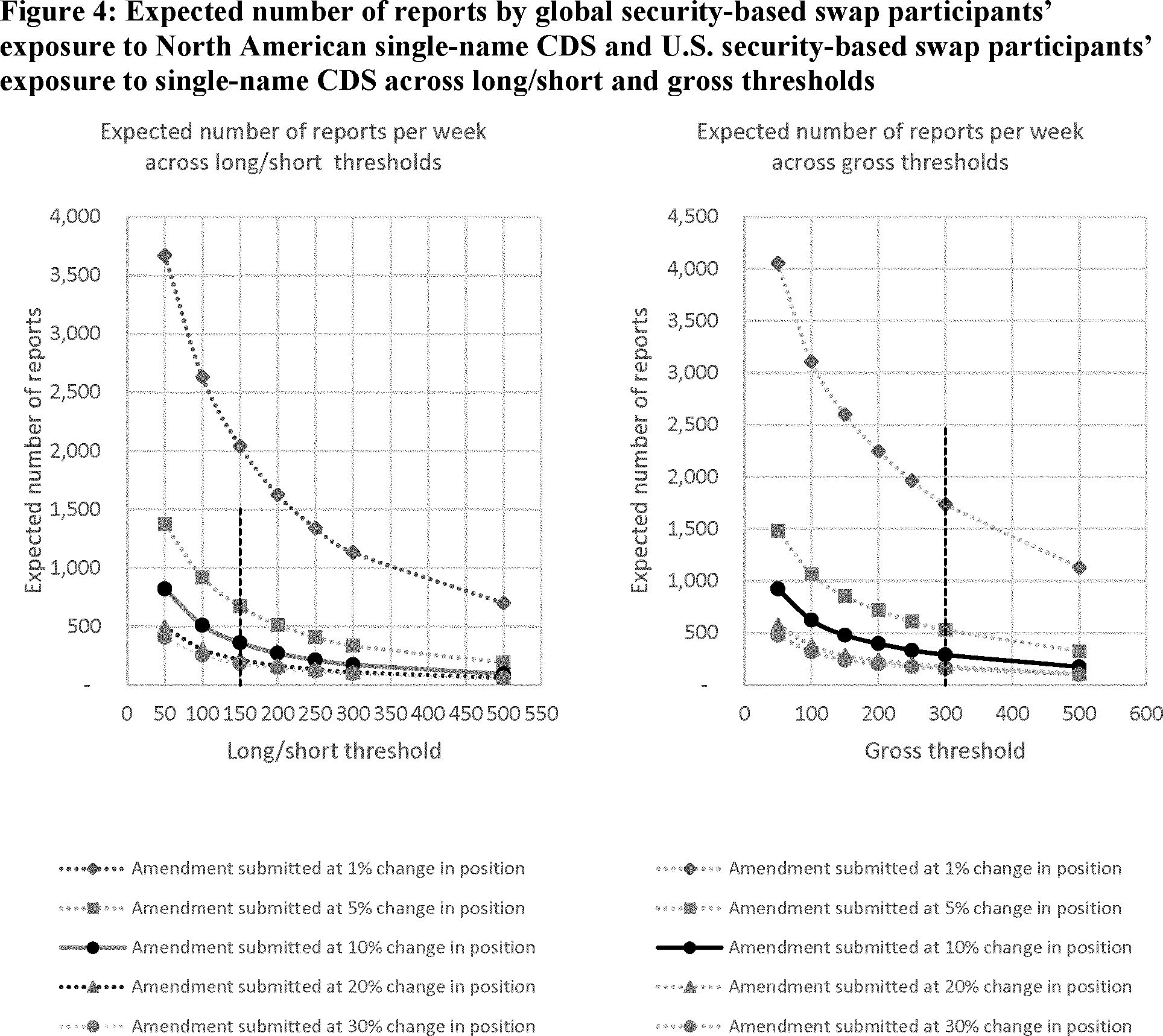

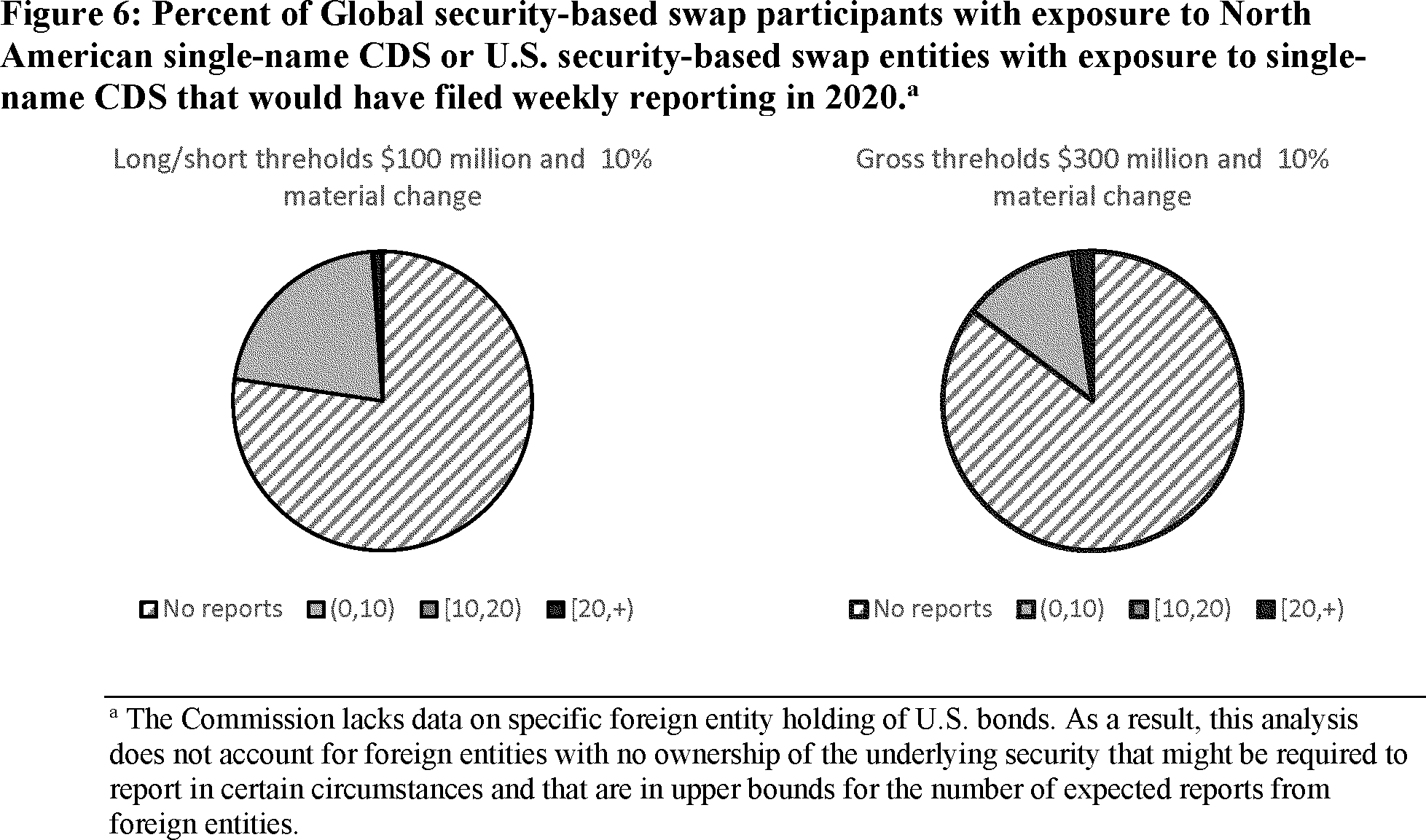

iii. Reporting Thresholds

(A) Thresholds for Credit Default Swaps

(B) Thresholds for Non-CDS Debt Security-Based Swaps and Security-Based Swaps on Equity

E. Reasonable Alternatives

1. Implementing a More Prescriptive Approach in Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1

2. Safe Harbor for Hedging Exposure Arising Out of Lending Activities

3. Mandating That Security-Based Swap Data Repositories Report or Publicly Disclose Positions

4. Adopting Position Limits

5. Threshold Alternatives for Security-Based Swaps Based on Equity and Non-CDS Debt 173

6. Threshold Alternatives for Credit Default Swaps

7. Information Required To Be Reported on Schedule 10B

F. Request for Comment

VII. Consideration of Impact on the Economy

VIII. Regulatory Flexibility Act Certification

IX. Statutory Authority

I. Introduction

A. Background

Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank Act”),[1] which established a regulatory framework for the over-the-counter (“OTC”) derivatives market, provides that the Commission is primarily responsible for regulating security-based swaps, while the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) is primarily responsible for regulating swaps. The Commission has now finalized a majority of its Title VII rules related to security-based swaps.[2] In accordance with those rules, a person who satisfies the definitions of “security-based swap dealer” (“SBSD”) or “major security-based swap participant” (“MSBSP”) (each SBSD and each MSBSP also referred to as an “SBS Entity” and together referred to as “SBS Entities”) is now required to register with the Commission in such capacity and is therefore subject to the Commission’s regime regarding margin, capital, segregation, recordkeeping and reporting, trade acknowledgment and verification requirements, risk mitigation techniques for uncleared security-based swaps, business conduct standards for security-based swap activity, including internal supervision requirements and the requirement to designate an individual to serve as the CCO who must take reasonable steps to ensure that the SBS Entity establishes, maintains, and reviews written policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with the Exchange Act and the rules and regulations thereunder relating to its business as an SBS Entity.[3] Transaction reporting for security-based swaps has been required since November 8, 2021, with public dissemination to begin on February 14, 2022.[4]

In addition to the operational rules for SBS Entities and security-based swap data reporting and public dissemination, the Dodd-Frank Act also amended the Exchange Act in a number of important ways to prohibit fraud, manipulation, and deception in connection with security-based swaps. In particular, Section 763(g) of the Dodd-Frank Act expanded the anti-manipulation provisions of Section 9 of the Exchange Act to encompass purchases or sales of security-based swaps and requires the Commission to adopt rules to prevent fraud, manipulation, and deception in connection with security-based swaps. Specifically, paragraph (j) of Section 9 makes it unlawful for “any person, directly or indirectly, by the use of any means or instrumentality of interstate commerce or of the mails, or of any facility of any national securities exchange, to effect any transaction in, or to induce or attempt to induce the purchase or sale of, any security-based swap, in connection with which such person engages in any fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative act or practice, makes any fictitious quotation, or engages in any transaction, practice, or course of business which operates as a fraud or deceit upon any person.” [5] It also provides that the Commission “shall . . . by rules and regulations define, and prescribe means reasonably designed to prevent, such transactions, acts, practices, and courses of business as are fraudulent, deceptive, or Start Printed Page 6654 manipulative, and such quotations as are fictitious.” [6]

Additionally, Section 761 of the Dodd-Frank Act modified several definitions in both the Exchange Act and the Securities Act to account for security-based swaps. For example, the Dodd-Frank Act amended the definition of “security” in Section 3(a)(10) of the Exchange Act [7] and Section 2(a)(1) of the Securities Act [8] to include security-based swaps. As a result, security-based swaps, because they are securities, are subject to the general antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the Federal securities laws, including Sections 9(a), 10(b) and 17 CFR 240.10b-5 (“Rule 10b-5”) under the Exchange Act,[9] and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act.[10]

Moreover, the Dodd-Frank Act amended the definitions of “purchase” and “sale” in Section 2(a)(18) of the Securities Act,[11] the definitions of “buy” and “purchase” in Section 3(a)(13) of the Exchange Act,[12] and “sale” and “sell” in Section 3(a)(14) of the Exchange Act,[13] in the context of security-based swaps, to include the execution, termination, assignment, exchange, transfer, or extinguishment of rights or obligations. As a result of those changes, misconduct in connection with these actions will also be prohibited under Sections 9 and 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act.

Finally, the Dodd-Frank Act also amended the Exchange Act to explicitly authorize the Commission to require reporting of large security-based swap positions. Section 763(h) of the Dodd-Frank Act, entitled “Position limits and position accountability for security-based swaps and large trader reporting,” added Section 10B to the Exchange Act. In addition to providing the Commission with authority to establish position limits for security-based swaps, Section 10B(d) also provides the Commission with rulemaking authority to require reporting of large security-based swap positions. Specifically, Section 10B(d) authorizes the Commission to:

. . . require any person that effects transactions for such person’s own account or the account of others in any securities-based swap or uncleared security-based swap and any security or loan or group or narrow-based security index of securities or loans . . . to report such information as the Commission may prescribe regarding any position or positions in any security-based swap or uncleared security-based swap and any security or loan or group or narrow-based security index of securities or loans and any other instrument relating to such security or loan or group or narrow-based security index of securities or loans . . .[14]

On November 3, 2010, the Commission proposed for comment new Rule 9j-1, which would have prohibited the same categories of misconduct as Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933, in the context of security-based swaps, but would also have explicitly addressed misconduct that is in connection with the “exercise of any right or performance of any obligation under” a security-based swap.[15] In other words, the 2010 proposed rule would have applied to offers, purchases, and sales of security-based swaps in the same way that the general antifraud provisions apply to all securities, but also would have explicitly applied to the cash flows, payments, deliveries, and other ongoing obligations and rights that are specific to security-based swaps.[16]

The Commission has not yet finalized rules mandated by Section 9(j), nor has it proposed any reporting requirements pursuant to Section 10B(d) of the Exchange Act. The regulatory landscape for security-based swaps has changed since the Commission first proposed Rule 9j-1 in 2010. At the time, efforts to reform the global OTC derivatives markets, which had been set in motion in response to the 2008 financial crisis, had only begun, such that these markets were not yet subject to a comprehensive regulatory framework.[17] Since that time, however, regulators overseeing the world’s primary OTC derivatives markets have made significant progress implementing reforms for OTC derivatives.[18] In addition to the progress made by the Commission in finalizing its Title VII rulemakings related to security-based swaps, the CFTC has largely completed its Title VII rulemakings related to swaps, including by adopting antifraud and anti-manipulation rules under the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA”) to implement the Dodd-Frank Act’s amendments to Section 6(c) of the CEA.[19] In light of the above, the Commission believes that now is an opportune time to move forward with the antifraud and manipulation rules required by Section 9(j) as well the rules contemplated by Section 10B(d). In addition, in recognition of the fact that CCOs of SBS Entities play an important role in preventing fraud and manipulation by SBS Entities and their personnel, in that they are tasked with designing and maintaining effective compliance systems, the Commission also is proposing an additional measure under Section 15F(h) of the Exchange Act to protect CCOs in the furtherance of those duties.[20]

B. Observations in the Credit Default Swap Market

In addition to the regulatory developments, there have been market developments. A number of press reports and academic articles since 2010 Start Printed Page 6655 have discussed manufactured credit events or other opportunistic strategies in the credit default swap (“CDS”) market.[21] Manufactured or other opportunistic CDS strategies can take a number of different forms but generally involve CDS buyers or sellers taking steps, with or without the participation of a company whose securities underlie, or are referenced by, a CDS (a “reference entity”),[22] to avoid, trigger, delay, accelerate, decrease, and/or increase payouts on CDS.[23] Some examples reported by academics and the press include:

• A CDS buyer working with a reference entity to create an artificial, technical, or temporary failure-to-pay credit event in order to trigger a payment on a CDS to the buyer (and to the detriment of the CDS seller).[24]

• The strategy above (as well as other strategies) can be combined with causing the reference entity to issue a below-market debt instrument in order to artificially increase the auction settlement price for the CDS ( i.e., by creating a new “cheapest to deliver” deliverable obligation).[25]

• CDS buyers endeavoring to influence the timing of a credit event in order to ensure a payment (upon the triggering of the CDS) before expiration of a CDS, or a CDS seller taking similar actions to avoid the obligation to pay by ensuring a credit event occurs after the expiration of the CDS, or taking actions to limit or expand the number and/or kind of deliverable obligations in order to impact the recovery rate.[26]

• CDS sellers offering financing to restructure a reference entity in such a way that “orphans” the CDS—eliminating or reducing the likelihood of a credit event by moving the debts off the balance sheets of the reference entity and onto the balance sheets of a subsidiary or an affiliate that is not referenced by the CDS.[27]

• Taking actions, including as part of a larger restructuring, to increase (or decrease) the supply of deliverable obligations by, for example, adding (or removing) a co-borrower to existing debt of a reference entity, thereby increasing (or decreasing) the likelihood of a credit event and the cost of CDS.[28]

In June 2019, the former SEC Chairman, together with the principals of the CFTC and the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority at the time, issued a public statement stating that the “continued pursuit of various opportunistic strategies in the credit derivatives markets, including but not limited to those that have been referred to as `manufactured credit events,’ may adversely affect the integrity, confidence and reputation of the credit derivatives markets, as well as markets more generally” (“2019 Joint Statement”).[29] Additionally, in April 2018 the Board of Directors of ISDA stated their belief that “narrowly tailored defaults . . . could negatively impact the efficiency, reliability and fairness of the overall CDS market.” [30] Following this statement, in March 2019, ISDA introduced amendments to its Credit Derivatives Definitions designed to address certain issues related to manufactured credit events, which ISDA termed “narrowly tailored credit events” (“ISDA Amendments”).[31]

C. Overview of the Proposal

1. Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1

The Commission has decided to re-propose Rule 9j-1. As described in detail below, re-proposed Rule 9j-1 follows the same general approach as the 2010 proposed rule in that it would prohibit the same categories of misconduct as Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act of 1933 in the context of security-based swaps, including misconduct that is in connection with the exercise of any right or performance of any obligation under a security-based swap.[32] Unlike the 2010 proposed rule, however, this new proposal also includes an anti-manipulation provision similar to 17 CFR 108.2 (“CFTC Rule 180.2”).[33] Further, re-proposed Rule 9j-1 would provide that: (1) A person with material non-public information about a security cannot avoid liability under the securities laws by making purchases or sales in the security-based swap (as opposed to purchasing or selling the underlying security), and (2) a person cannot avoid liability under Section 9(j) or re-proposed Rule 9j-1 in connection with a fraudulent scheme involving a security-based swap by instead making purchases or sales in the underlying Start Printed Page 6656 security (as opposed to purchases or sales in -the security-based swap).[34]

The Commission recognizes that CDS buyers and sellers regularly engage in legitimate interactions with reference entities, and often offer critical means of restructuring and funding for reference entities. Moreover, we also understand that CDS transactions are an important means by which debt holders hedge their underlying debt instruments, and that the absence of such hedging opportunities could impact prospective investors’ willingness and ability to invest in that underlying market. The Commission preliminarily believes the proposal is sufficiently tailored to balance these concerns but, in section II.E below, is also soliciting comment on how it can address manufactured or other opportunistic strategies that involve fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative activity, or that involve such quotations as are fictitious, without impairing the proper functioning of the security-based swap markets or other securities markets.

Further, the scope of re-proposed Rule 9j-1 is not limited to CDS. Fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative conduct, such as providing false or incomplete information to a counterparty to secure better terms or pricing or to alter the performance of ongoing rights and obligations, has the potential to harm counterparties to all forms of swaps, including equity and non-CDS debt security-based swaps. Manipulation of the underlying reference security can affect the pricing of an equity or debt security-based swaps, as well as the ongoing payments and obligations that are based on the value of that reference security. Further, in some cases, particularly in instances involving security-based swaps transactions that are effected over the internet, there is a potential for trading software to distort pricing and payouts on security-based swaps.[35] Finally, to the extent an opportunistic strategy alters the operations of a reference entity, counterparties to any security-based swap based on that reference entity could be impacted; the potential harm is not limited to CDS holders. As a result, re-proposed Rule 9j-1 applies to all transactions in security-based swaps, consistent with the 2010 proposed rule.

2. Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c)

The Commission also is proposing a rule aimed at protecting the independence and objectivity of an SBS Entity’s CCO by preventing the personnel of an SBS Entity from taking actions to coerce, mislead, or otherwise interfere with the CCO. The Commission recognizes that SBS Entities dominate the security-based swap market and also recognizes the important role that CCOs of SBS Entities play in ensuring compliance by SBS Entities and their personnel with the federal securities laws. As a result, the Commission is proposing Rule15Fh-4(c) which would make it unlawful for any officer, director, supervised person, or employee of an SBS Entity, or any person acting under such person’s direction, to directly or indirectly take any action to coerce, manipulate, mislead, or fraudulently influence the SBS Entity’s CCO in the performance of their duties under the Federal securities laws or the rules and regulations thereunder.

3. Proposed Rule 10B-1

Finally, the Commission also recognizes that transparency can be beneficial to market participants so that they can act in an informed manner to protect their own interests. One example involves what some legal observers refer to as “net-short debt activism”—where a market participant with a large CDS position and a controlling voting interest in the debt of a reference entity votes against its interest as a debt holder to ensure that a credit event occurs (such as by blocking a restructuring or voting against curing a technical default under the terms of a loan).[36] In such instances, both the Commission and relevant market participants—particularly issuers of the underlying debt securities—could benefit from having access to information that may indicate that one or more market participants has a financial incentive to take an action that would be harmful to the issuer, which in turn could impact the issuer’s other security holders.[37] In particular, such notice would provide the relevant parties with the ability to take appropriate action to limit any potential harmful consequences. Given such benefits to the market, which may accrue even where the facts and circumstances of a particular situation are not indicative of potentially fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct, the Commission believes that public reporting of large CDS positions would help to provide such advance notice.

Additional transparency regarding large security-based swap positions also could alert market participants, including counterparties, as well as issuers of securities and their security holders, to the risk posed by the concentrated exposure of a counterparty. Such transparency also could enhance risk management by security-based swap counterparties and inform pricing of the security-based swaps. For example, if a single counterparty has a $5 billion security-based swap position distributed equally among five different dealers on the same underlying equity security, public reporting of that security-based swap position would alert each dealer to the total exposure of the reporting counterparty. In the event of an issue involving the underlying security or the counterparty’s ability to make a payment on the security-based swaps composing the large position, some or all of those dealers could then take actions to protect their positions, such as increasing their hedges against the relevant security-based swaps or calling for additional margin, if permitted. Knowledge of the total position of a counterparty also may inform a dealer’s actions in the event that the counterparty defaults on its obligations under the security-based swap.

Finally, transparency about security-based swap positions could play an important role in protecting market integrity, including by providing the Commission and other regulators with access to information that may indicate that a person (or a group of persons) is building up a large security-based swap position, which may be relevant for a number of reasons, as discussed in greater detail in section III. As previously discussed, the manufactured or other opportunistic strategies that have been reported to have taken place in the CDS markets take on a variety of Start Printed Page 6657 forms. Although some of those strategies may have involved fraudulent or manipulative conduct, including those that involve parties acting to artificially inflate CDS payments, others do not necessarily constitute prohibited activity. The common thread to all of those strategies, however, is one or more parties taking affirmative steps to avoid, trigger, delay, accelerate, decrease, and/or increase payouts on CDS.[38] Given the importance of the CDS market and its interconnectedness with the underlying debt securities that CDS may be used to hedge, the Commission believes that additional transparency in the CDS market can help to ensure that it remains fair, orderly, and efficient. For similar reasons, such transparency also should benefit the market for other types of security-based swaps.

Accordingly, the Commission has decided to utilize its rulemaking authority under Section 10B of the Exchange Act to propose new Rule 10B-1, which would be a large trader position reporting rule for security-based swaps. Specifically, proposed Rule 10B-1 would require public reporting of, among other things: (1) Certain large positions in security-based swaps; (2) positions in any security or loan underlying the security-based swap position; and (3) positions in any other instrument relating to the underlying security or loan or group or index of securities or loans. As described in detail below, proposed Rule 10B-1 would, among other things, include a specific quantitative threshold for when public reporting is required.

The Commission recognizes that market participants are already subject to the requirements of 17 CFR 242.900 through 242.909 (“Regulation SBSR”), which governs regulatory reporting of security-based swap transactions to security-based swap data repositories (“SBSDRs”) and public dissemination of some of that transaction data pursuant to Section 13(m) of the Exchange Act.[39] Although both sets of requirements are intended to provide greater transparency in the security-based swap market, certain differences between the two highlight the need to propose Rule 10B-1. For example, pursuant to the statutory authority in Section 13(m)(1), Regulation SBSR requires real-time public reporting to SBSDRs and public dissemination of security-based swap transaction data but not of position data as is contemplated by Section 10B and proposed Rule 10B-1.[40] Although registered SBSDRs are required to establish, maintain, and enforce written policies and procedures reasonably designed to calculate positions for all persons with open security-based swaps for which the SBSDR maintains records,[41] they are not required to make those reports public.[42] As a result, any public position reporting pursuant to Regulation SBSR would need to be completely anonymous with respect to both the person building up large, concentrated security-based swap positions, and each of its counterparties. Finally, Regulation SBSR only requires reporting and public dissemination of security-based swaps, in contrast to Section 10B, which authorizes the Commission to require reporting of positions in both security-based swaps and related securities.[43] The Commission believes that requiring reporting of related securities serves an important function in allowing both the Commission and the public to develop a greater understanding of the impact that a large security-based swap position can have on the broader securities markets.

II. Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1: Prohibition Against Fraud, Manipulation, and Deception in Connection With Security-Based Swaps

A. Prior Commission Action

As initially proposed in 2010, Rule 9j-1 would have prohibited the same categories of misconduct addressed by Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act [44] and Rule 10b-5 thereunder,[45] as well as Section 17(a) of the Securities Act,[46] but specifically in the context of security-based swaps. The 2010 proposed rule explicitly reached misconduct in connection with the ongoing payments and deliveries that are typical of security-based swaps, which occur throughout the life of the security-based swap.[47] Specifically, the 2010 proposed rule would have made it unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, in connection with the offer, purchase or sale of any security-based swap, in the exercise of any right or performance of any obligation under a security-based swap, or the avoidance of such exercise or performance: (a) To employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud or manipulate; (b) to knowingly or recklessly make any untrue statement of a material fact, or to knowingly or recklessly omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading; (c) to obtain money or property by means of any untrue statement of a material fact or any omission to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading; or (d) to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person.[48]

Most commenters on the 2010 proposed rule generally supported the Commission’s goal of adopting antifraud standards to ensure the integrity of the security-based swap market.[49] Some commenters expressed strong support for the 2010 proposed rule, stating that the rule would encourage investor confidence in the security-based swap market and would help ensure that the Commission has the ability to respond through enforcement mechanisms to Start Printed Page 6658 misconduct interfering with the independence and proper functioning of the market.[50] In addition, one commenter specifically requested that the Commission require disclosure of debt security-based swap positions.[51]

However, some commenters stated that the 2010 proposed rule exceeded the Commission’s authority by addressing activities involving the exercise of any rights and performance of any obligations during the life of a security-based swap, as opposed to addressing only misconduct taking place in connection with the “purchase” and “sale” of a security-based swap.[52] Those commenters all generally argued that unless modified, the 2010 proposed rule would have a negative impact or chilling effect on the security-based swap market by unintentionally prohibiting the legitimate exercise of rights and performance of obligations under a security-based swap and by leading to costly unintended consequences. Section II.B.2. includes a discussion of the concerns raised by these commenters.

B. Scope of Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1

1. General Antifraud and Anti-Manipulation Provisions

The general antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions in re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) would make it unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly, (i) to purchase or sell, or attempt to induce the purchase or sale of, any security-based swap; [53] (ii) to effect any transaction in, or attempt to effect any transaction in, any security-based swap; (iii) to take any action to exercise any right, or any action related to performance of any obligation, under any security-based swap, including in connection with any payments, deliveries, rights, or obligations or alterations of any rights thereunder; or (iv) to terminate (other than on its scheduled maturity date) or settle any security-based swap, in connection with which such person:

(1) Employs or attempts to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud or manipulate; or

(2) Makes or attempts to make any untrue statement of a material fact, or omits to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading; or

(3) Obtains or attempts to obtain money or property by means of any untrue statement of a material fact or any omission to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading; or

(4) Engages or attempts to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person.

Like the 2010 proposed rule, the current proposal generally relies on language from Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act [54] and Rule 10b-5 thereunder,[55] and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act,[56] as it relates to the specific types of fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct that re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) is designed to address. In addition, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) describes the particular types of activity that would be covered by the rule, to the extent that a person engages in specified types of fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct in connection with such activities.[57] Specifically, the proposed rule would apply not only to the “purchase” or “sale” of security-based swaps, as such terms are defined in the Exchange Act,[58] but also to: (1) Effecting transactions, or attempts to effect transactions in, security-based swaps, (2) taking actions to exercise any right or actions related to performance of any obligation pursuant to any security-based swap including any payments, deliveries, rights, or obligations or alterations of any rights thereunder, or (3) terminating (other than on its scheduled maturity date) or settling any security-based swap, in connection with which such person engages in the specified fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct.

With respect to the operative paragraphs in re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) describing the fraudulent, manipulative or deceptive conduct that the rule prohibits, those provisions have been structured to combine the antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions in Rule 10b-5 that apply to all securities (including security-based swaps) with the additional antifraud and anti-manipulative authority specific to security-based swaps provided to the Commission in Section 9(j). For example, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a)(1) would explicitly prohibit employing or attempting to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud or manipulate. Although most of that language is derived from Section 10(b) Start Printed Page 6659 of the Exchange Act,[59] Rule 10b-5 thereunder,[60] and Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act,[61] the inclusion of “manipulate” and the extension of the prohibition to include an “attempt” to employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud or manipulate comes directly from the statutory authority in Section 9(j).[62] Paragraph (a)(2) of re-proposed Rule 9j-1, which prohibits the making of material misstatements or omissions, also is based on Rule 10b-5 and also contemplates an attempt to make a material misstatement or omission.

Finally, paragraphs (a)(3) and (4) of re-proposed Rule 9j-1 are based on Sections 17(a)(2) and (3) of the Securities Act.[63] Again, however, the re-proposed rule would now extend those provisions to attempted conduct, such that they would prohibit a person from (i) obtaining or attempting to obtain money or property by means of any untrue statement of a material fact or any omission to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in light of the circumstances under which they were made, not misleading; and (ii) engaging or attempting to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person.

As the Commission explained in the 2010 Rule 9j-1 Proposing Release, the provisions described above have been designed generally to prohibit a range of fraudulent, manipulative and deceptive conduct in the security-based swap market, such as, among other things, “engaging in fraudulent and deceptive schemes in order to increase or decrease the price or value of a security-based swap, or disseminating false or misleading statements that affect or otherwise manipulate the price or value of the reference underlying of a security-based swap for the purpose of benefiting such person’s position in the security-based swap.” [64] Re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) also would prohibit, for example, disseminating false financial information or data in connection with the sale of a security-based swap or insider trading in a security-based swap. It also would prevent misconduct that affects the market value of the security-based swap for purposes of posting collateral or making payments or deliveries under such security-based swap.[65]

Re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) also would prohibit fraudulent conduct in connection with a security-based swap that affects the value of cash flow, payments, or deliveries, such as by triggering the obligation of a counterparty to make a large payment or to post additional collateral. It would also prohibit a person from taking fraudulent or manipulative action with respect to the reference entity or asset of the security-based swap that triggers the exercise of a right or performance of an obligation or affects the payments to be made.[66]

Re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(1) and (2), consistent with Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder,[67] and Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act,[68] would require scienter.[69] In contrast, re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(3) and (4) would not require scienter consistent with Sections 17(a)(2) and (3) of the Securities Act.[70]

While both re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(2) and (3) would prohibit material misstatements and omissions,[71] they would address different levels of culpability.[72] Specifically, re-proposed Start Printed Page 6660 Rule 9j-1(a)(2) would apply when there is evidence of scienter ( e.g., when a party to a security-based swap knowingly or recklessly makes a false statement even though the party may not receive any money or property as a result). In contrast, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a)(3) would extend to conduct that is at least negligent ( e.g., when a party to a security-based swap knows or reasonably should know that a statement was false or misleading and directly or indirectly obtains money or property by means of such statement).

The Commission recognizes that two commenters to the 2010 proposed rule opposed not requiring scienter with respect to paragraphs (3) and (4) of re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) (which were paragraphs (c) and (d) in the 2010 proposed rule). Specifically, SIFMA and ISDA argued that applying a negligence standard to those provisions did not account for the unique aspects of the security-based swap market and, when “coupled with the rights and responsibilities provision and enforcement exposure for omissions of disclosure, potentially would make illegal a wide range of ordinary course activities that may relate to an SBS transaction.” [73] Those commenters explained that “[s]ubjecting every trading decision or payment under an SBS to an enforcement claim that someone knew or should have known that the action would operate as a fraud or deceit on a person could potentially deter many parties from entering into SBS, increase their cost and have other distorting effects on the markets.” [74]

Although the Commission recognizes the concerns raised by these commenters, we have determined to re-propose Rule 9j-1(a) using the same standards of care as proposed in 2010. As previously noted, each of those provisions is based on an existing statutory and regulatory provision that is supported by a large body of case law.[75] In that respect, the Commission does not believe it is appropriate to treat negligent conduct that would have been deemed a violation under the existing antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the Federal securities laws and the rules and regulations thereunder as not violative under proposed Rule 9j-1(a) solely because security-based swaps contracts by their nature may require the counterparties to take ongoing actions to satisfy their rights and obligations. Such an approach would be particularly untenable in light of the fact that security-based swaps are included in the definition of “security”, and therefore are also subject to such general antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions, including the relevant non-scienter-based prohibitions. To the extent that there is any overlap between re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) and those existing provisions, introducing a different standard of care would create unnecessary confusion.

Moreover, having two nearly identical antifraud and anti-manipulation rules ( e.g., re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a)(1) and Rule 10b-5(b)) that are subject to two different standards of care—one for security-based swaps and one for other types of securities—is likely to lead to confusion among market participants and could potentially undermine the effectiveness of both provisions in certain circumstances, such as when the case law applicable to one provision contradicts the other in a way that is not able to be rationalized by the differences in the underlying instruments. Although the Commission preliminarily believes the re-proposed rule is not overly broad, in section II.E below, the Commission is requesting comment on whether there are potential ways to minimize the impact of the rule on non-fraudulent and non-manipulative ordinary course activities in connection with security-based swap transactions.

2. “Purchases” and “Sales” in the Context of Security-Based Swaps and Limited Safe Harbor for Certain Limited Actions

As previously noted, a number of commenters on the 2010 proposed rule argued that the Commission exceeded its statutory authority in the course of proposing Rule 9j-1 by explicitly applying the rule to activities involving the exercise of any rights and performance of any obligations during the life of a security-based swap, as opposed to limiting the proposed rule to misconduct taking place in connection with the “purchase” and “sale” of a security-based swap.[76] For example, MFA argued that the Commission exceeded delegated authority in proposing that the prohibitions in Rule 9j-1 extend “beyond purchases and sales to acts and omissions occurring during the term of a security-based swap,” explaining that “[i]n clarifying the terms `purchase’ and `sale’ in the security-based swap context, Congress chose specifically not to include ongoing obligations, which are dictated by the contract between the two parties underlying the security-based swap and which bear no relation to execution, termination, assignment, exchange and transfer or extinguishment of rights.” [77] MFA also expressed its view that “Section 763(g) of Dodd-Frank is aimed at preventing fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative acts in connection with: (i) The entry into a securit[y]-based swap; (ii) the novation or assignment of a securit[y]-based swap; and (iii) the unwind of a securit[y]-based swap,” and that the statute should not be read to encompass the settlement of a security-based swap, or the ongoing payments or collateral postings that take place throughout the life of the transaction.[78]

Similarly, SIFMA and ISDA expressed the view that “[t]he rulemaking authority provided by Section 763(g) only extends to transactions, acts, practices, or courses of business in connection with (i) effecting any transaction in [a security-based swap] and (ii) inducing or attempting to induce the purchase or sale of [a security-based swap].” [79] SIFMA also separately shared its concerns that the application of proposed Rule 9j-1 to the ongoing, “non-volitional” rights and obligations that occur throughout the life of a security-based swap could be particularly problematic in the event that a counterparty came into possession of material non-public information relating to the underlying security, even if such information had no bearing on such non-volitional actions.[80] Further, the LSTA argued that Start Printed Page 6661 the 2010 proposed rule would “create uncertainty that undermines investors’ willingness to enter [the security-based swap] market,” explaining that if the rule were to apply to any activity that potentially affects the stream of payments, deliveries or other ongoing obligations or rights between parties to a security-based swap, “each party will have to implement controls and mechanisms to track decisions it may take that could affect each such payment, delivery, obligation or right as well as to track changes in its positions in the security-based swap and reference underlying.” [81]

The Commission has carefully considered these comments, but disagrees with the narrow interpretation of the terms “purchase” and “sale” when used in the context of security-based swaps, as espoused by commenters. Specifically, the Commission does not believe that the definitions of “purchase” and “sale” in Section 2(a)(18) of the Securities Act, the definitions of “buy” and “purchase” in Section 3(a)(13) of the Exchange Act, and the definitions of “sale” and “sell” in Section 3(a)(14) of the Exchange Act are limited to actions involving all of the rights and obligations under a security-based swap. Rather, the Commission believes that those definitions incorporate partial executions, terminations, assignments, exchanges, transfers, or extinguishments of rights or obligations. Put another way, those definitions incorporate actions that have an impact on some, but not all, rights and obligations, such as a margin payment that represents only part of what one counterparty owes the other.

In addition, Congress could have specifically limited the statutory definitions of “purchase” or “sale” to actions involving all of the rights and obligations under a security-based swap, and the Commission, therefore, does not believe it necessary to apply limitations to those definitions that do not appear in the statute given that even partial payments or deliveries over the course of a security-based swap are likely to be meaningful to most security-based swap transactions. Accordingly, we continue to believe the statute provides the Commission with authority to make explicit the liability of persons that engage in misconduct to trigger, avoid, or affect the value of ongoing payments or deliveries as a means reasonably designed to prevent fraud, manipulation, and deception in connection with security-based swap transactions.

To be clear, the Commission is not taking the position that every payment or delivery made during the course of a security-based swap transaction is itself a purchase or sale of a security-based swap under the applicable statutory authority. Rather, fraudulent or manipulative conduct would be in connection with the purchase or sale of a security-based swap if it either alters any material terms of the security-based swap (as set forth in the applicable trading relationship documentation) or has a material impact on any payment or delivery under the security-based swap, such that it would not be consistent with what a reasonable person would have expected to pay, deliver, or receive absent such conduct. The Commission took a similar position when it defined certain Title VII terms, including “swap” and “security-based swap,” in a joint release with the CFTC, explaining that “[i]f the material terms of a Title VII instrument are amended or modified during its life based on an exercise of discretion and not through predetermined criteria or a predetermined self-executing formula, the Commissions view the amended or modified Title VII instrument as a new Title VII instrument.” [82] If a party engages in fraudulent or manipulative conduct that impacts the amount of payment or delivery in a way that is materially different from the amount a reasonable person would have expected to pay, deliver, or receive (or where such person would not have expected a payment or delivery to be required at all), such actions would be a new purchase or sale of the security-based swap. For example, and without limitation, such a scenario could involve a counterparty misstating certain information about a transaction (or any related transactions) resulting in a missed or late payment or loss of an opportunity to request additional collateral under a security-based swap.

Moreover, even if those statutory definitions were interpreted narrowly, the Commission’s rulemaking authority under Section 9(j) of the Exchange Act to adopt prophylactic rules is not limited solely to purchases and sales of security-based swaps.[83] Section 9(j) of the Exchange Act provides that the Commission “shall . . . by rules and regulations define, and prescribe means reasonably designed to prevent, such transactions, acts, practices, and courses of business as are fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative, and such quotations as are fictitious.” [84] Without limiting what is already covered by Section 9(j), the Commission is using that statutory authority to prohibit actions to exercise any right, or any action related to performance of any obligation, under any security-based swap, including in connection with any payments, deliveries, rights, or obligations or alterations of any rights thereunder; or to terminate (other than on its scheduled maturity date) or settle any security-based swap, in each case so long as those actions are taken in connection with fraud, manipulation, or deception. The Commission believes that by prohibiting actions that directly impact a counterparty’s rights and obligations under a security-based swap—when such actions are in connection with specified fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct—re-proposed Rule 9j-1 represents a means reasonably designed to prevent fraud, manipulation, and deception in the security-based swap market.

Furthermore, in the course of using its rulemaking authority under Section 9(j), the Commission looked not only to the antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions in Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act, Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, but also to the operative provisions of Section 9(j) itself, which makes it unlawful “to effect any transaction in, or to induce or attempt to induce the purchase or sale of, any security-based swap, in connection with which such person engages in any fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative act or practice, makes any fictitious quotation, or engages in any transaction, practice, or course of business which operates as Start Printed Page 6662 a fraud or deceit upon any person.” At a minimum, that provision prohibits fraud, manipulation, or deception in the context of both inducements or attempts to induce the purchase or sale of a security-based swap, and effecting security-based swap transactions. As the Commission has previously explained in other contexts, “effecting” transactions in securities has been interpreted broadly and includes more than just executing trades or forwarding orders for execution.[85] Generally, effecting securities transactions also can include, for example, participating in the transactions through a number of activities such as screening potential participants in a transaction for creditworthiness, facilitating the execution of a transaction, and handling customer funds and securities.[86]

As discussed above, we disagree with the narrow interpretation of the statutory changes to the definitions of “purchase” and “sale” in the context of a security-based swap, as suggested by some commenters. That said, the Commission is sensitive to the operational concerns raised by commenters in response to the 2010 proposed rule and is therefore proposing two limited safe harbors from re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) to address situations when a counterparty to a security-based swap is required to take certain actions while in possession of material non-public information.[87]

Specifically, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(f)(1) would provide that a person would not be liable under re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) solely for reason of being aware of material non-public information while taking certain actions, the first of which includes actions taken in accordance with binding contractual rights and obligations under a security-based swap (as reflected in the written security-based swap documentation governing such transaction or any amendment thereto) so long as the person could demonstrate that: (1) The security-based swap was entered into, or the amendment was made, before the person became aware of such material non-public information; and (2) that the entry into, and the terms of, the security-based swap are themselves not a violation of any provision of re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a).[88] The Commission believes that limiting the safe harbor to circumstances where the activity is taken in accordance with the written agreements governing the security-based swap would help to ensure that such action is taken in the ordinary course of the transaction. Further, the safe harbor would apply only so long as the entry into, and the terms of, the security-based swap do not otherwise violate re-proposed Rule 9j-1.

As a result, the proposed safe harbor would generally apply to, for example, making a standardized coupon payment or delivering collateral to a counterparty (and would also permit the counterparty to receive the coupon payment or collateral), while such person is aware of material non-public information, so long as both actions are explicitly required by the terms of the transaction and documented in writing. However, the safe harbor would not apply if a counterparty took some action to fraudulently increase (in the case of the receiving counterparty) or decrease (in the case of the delivering counterparty) the amount of such payment or collateral transfer.

The second proposed safe harbor would apply to transactions effected pursuant to certain types of compression exercises. Specifically, proposed Rule 9j-1(f)(2) would provide that a person would not be liable under re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) solely for reason of being aware of material non-public information when effecting security-based swap transactions pursuant to a bilateral portfolio compression exercise (as defined in 17 CFR 240.15Fi-1(a) (“Rule 15Fi-1(a)”) of the Exchange Act) or a multilateral portfolio compression exercise (as defined Rule 15Fi-1(j)) so long as: (1) Any such transactions are consistent with all of the terms of a bilateral portfolio compression exercise or multilateral portfolio compression exercise, including as it relates to, without limitation, the transactions to be included in the exercise, the risk tolerances of the persons participating in the exercise, and the methodology used in the exercise, and (2) all such terms were agreed to by all participants of the bilateral portfolio compression exercise or multilateral portfolio compression exercise prior to the commencement of the applicable exercise.[89]

As the Commission explained when it adopted portfolio compression requirements for SBS Entities, portfolio compression generally refers to a post-trade processing exercise that allows two or more market participants to eliminate redundant derivatives transactions within their portfolios in a manner that does not change their net exposure, and is intended to help market participants manage their post-traded risk.[90] For example, reducing the number of outstanding contracts provides important operational benefits and efficiencies for market participants in that there are fewer open contracts to Start Printed Page 6663 manage, maintain, and settle, resulting in fewer opportunities for processing errors, failures, or other problems that could develop throughout the lifecycle of a transaction.[91] Given these important benefits, as well as the largely administrative nature of the portfolio compression process, the Commission believes it to be appropriate to provide a safe harbor for this activity in circumstances where the security-based swap counterparty is in possession of material non-public information with respect to a reference entity underlying an applicable security-based swap.

However, the proposed safe harbor would apply only so long as: (1) Any such transactions are consistent with all of the terms of a bilateral portfolio compression exercise or multilateral portfolio compression exercise, including as it relates to, without limitation, the transactions to be included in the exercise, the risk tolerances of the persons participating in the exercise, and the methodology used in the exercise, and (2) all such terms were agreed to by all participants of the bilateral portfolio compression exercise or multilateral portfolio compression exercise prior to the commencement of the applicable exercise. This condition, which the Commission believes is consistent with how portfolio compression exercises typically operate, is intended to help ensure that most, if not all, of the opportunities to take a discretionary action to impact the outcome of the compression exercise occur before the process begins, and therefore before specific security-based swap transactions are identified to be added or eliminated. Finally, this safe harbor, which is limited to circumstances involving the misuse of material non-public information, would not apply where the portfolio compression exercise itself was part of a fraudulent or manipulative scheme to increase (in the case of the receiving counterparty) or decrease (in the case of the delivering counterparty) the amount of any payment made or received in connection with a terminated or replacement security-based swap transaction resulting from the portfolio compression exercise, as applicable.

3. Prohibition on Price Manipulation

In addition to the general antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions discussed above, re-proposed Rule 9j-1 also contains provisions designed to address price manipulation similar to CFTC Rule 180.2.[92] Specifically, re-proposed Rule 9j-1 includes a prohibition on attempted manipulation. Re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b) would make it unlawful for any person to, directly or indirectly, manipulate or attempt to manipulate the price or valuation of any security-based swap, or any payment or delivery related thereto. Among other things, this language is intended to address a number of the manufactured or other opportunistic CDS strategies observed over the last decade, and summarized above in section I.B, including situations where a party intentionally distorts any payment related to a security-based swap for the benefit of one of the security-based swap counterparties, such as actions that serve little to no economic purpose other than to artificially influence the composition of the deliverable obligations in a CDS auction.[93]

Re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b) also is intended to prohibit, among other things, a situation where a person (or group of persons) improperly and intentionally causes or avoids the purchase or sale of a security-based swap for the benefit of a counterparty to an SBS, such as intentionally and improperly orphaning a CDS, avoiding termination of a CDS for a period of time, or causing the termination of a CDS. As previously noted, “orphaning” a CDS refers to a situation where the debt of a reference entity is eliminated or reduced for the purposes of moving the price of CDS.[94] The end result of such activity is that CDS buyers continue to pay (and CDS sellers continue to receive) premiums on CDS that will never default. Similarly, a CDS protection seller could offer financing to the company to avoid a credit event and subsequent CDS payout, with the financing timed so that the company’s bankruptcy is merely delayed until after the CDS expires.[95] To be clear, a person simply profiting from a CDS position after a company’s bankruptcy, which such person could have prevented by participating in a financing to the company, without more is not in and of itself improper conduct for purposes of re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b).

Moreover, the Commission does not intend for re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b) to apply to taking affirmative actions in the ordinary course of a security-based swap transaction or the underlying referenced security. Specifically, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b) is designed to capture situations when a payment under the security-based swap is intentionally distorted. A determination as to whether a payment is intentionally distorted will largely depend on the facts and circumstances of each particular situation, but as a general matter the Commission would expect to use its authority to bring an enforcement action under re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b) when a party takes action for the purposes of avoiding or causing, or increasing or decreasing, a payment under a security-based swap in a manner that would not have occurred, but for such actions.

The Commission recognizes that reference entities often rely on financing and other forms of relief to avoid defaulting on their debt, and the proposed rule is not intended to discourage lenders and prospective lenders from discussing or providing such financing or relief, even when those persons also hold CDS positions. Rather, the Commission is proposing Rule 9j-1(b) to account for actions taken outside the ordinary course of a typical lender-borrower relationship (or a prospective lender-borrower relationship). Although any such determination would need to be based on the facts and circumstances of a particular situation, as a general matter the Commission believes that an action that appears to be designed almost exclusively to harm one or more CDS counterparties would likely fall within the prohibition in re-proposed Rule 9j-1(b).

C. Liability Under Proposed Rule 9j-1 in Connection With the Purchase or Sale of a Security

Finally, and consistent with the long-standing principle that parties cannot do indirectly what they are prohibited from doing directly, paragraphs (c) and (d) of re-proposed Rule 9j-1 would make it clear that market participants cannot avoid liability under the rule by effecting a fraudulent scheme through the purchase or sale of an underlying security, rather than the purchase or sale of the security-based swap on which it is based, and vice versa. The first of those two provisions would provide that a person could not escape liability for trading based on possession of material non-public information about a security by purchasing or selling a security-based swap based on that security (as opposed to trading in the security itself) and the second provision provides that a person could not escape liability under Section 9(j) or re-proposed Rule 9j-1 by purchasing or selling the underlying security (as opposed to purchasing or selling a security-based swap that is based on that security). Start Printed Page 6664

Specifically, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(c) would provide that wherever communicating, or purchasing or selling a security (other than a security-based swap) while in possession of, material non-public information would violate, or result in liability to any purchaser or seller of the security, under either the Exchange Act or the Securities Act, or any rule or regulation thereunder, such conduct in connection with a purchase or sale of a security-based swap with respect to such security or with respect to a group or index of securities including such security shall also violate, and result in comparable liability to any purchaser or seller of that security under, such provision, rule, or regulation. Rule 9j-1(c) would be modeled after Section 20(d) of the Exchange Act, which is substantially similar to the proposal, except that the statutory provision applies to “a put, call, straddle, option, privilege or security-based swap agreement”— i.e., it does not expressly include the term security-based swap.[96]

Although the Commission generally believes that a situation where a person uses material non-public information in a security in connection with the purchase and sale of a security-based swap would be subject to the existing antifraud authority under the Federal securities laws, particularly Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, the Commission also believes that market participants would benefit from a clarified interpretation of that statutory provision in this rulemaking.[97] This is particularly true given that the issuer of a security-based swap ( i.e., each counterparty to the transaction) is different from the issuer of the underlying security ( i.e., the reference entity). Accordingly, the Commission is now proposing new Rule 9j-1(c) to provide that a person making a purchase or sale of a security-based swap while in possession of material non-public information with respect to the security underlying such security-based swap is subject to liability.

Lastly, the Commission also is proposing new Rule 9j-1(d), which is intended to address a situation similar to the one described above, but in the other direction. Specifically, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(d) would provide that whenever purchasing or selling a security-based swap would violate, or result in liability under Section 9(j) of the Exchange Act or re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) or (b), such conduct, when taken by a counterparty to such security-based swap (or any affiliate of, or a person acting in concert with, such security-based swap counterparty in furtherance of such prohibited activity), in connection with a purchase or sale of a security or group or index of securities on which such security-based swap is based shall also violate, and shall be deemed a violation of, Section 9(j) or re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) or (b).

This provision is designed so that a person cannot escape liability under Section 9(j) or re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) or (b) with respect to a security-based swap by limiting all of its actions to purchases and sales of the security or narrow-based security index underlying that security-based swap. For example, if a person with an existing total return swap on equity securities issued by XYZ Corporation subsequently engages in a number of wash trades to artificially inflate the price of the equity securities in order to benefit from the manipulated price by way of their existing security-based swap position, such person would be liable for violations of Section 9(j) and re-proposed Rule 9j-1 regardless of the fact the manipulation was conducted through purchases and sales of the equity securities.

To be clear, re-proposed Rule 9j-1(d) is not intended to create a separate category of prohibited activity. Rather, this provision is designed to specify that many of the activities that would be considered fraud, manipulation, or deceit with respect to a security-based swap are typically effected through transactions in the underlying reference entity, security, loan, or group or index of securities or loans. The Commission believes that this provision is important to include in the rule because security-based swaps by their nature are tied intrinsically to activity in other securities markets.

Moreover, this provision is not intended to suggest that a person could be liable for violations of Section 9(j) and re-proposed Rule 9j-1 based solely on the impact of its transactions on the equity, debt, or loan markets. In that regard, the rule would state that the person engaged in prohibited activities in the equity, debt, or loan markets must be a counterparty to a security-based swap that references such equity or debt securities or loans, or be an affiliate of, or a person acting in concert with, such security-based swap counterparty in furtherance of such prohibited activity. Finally, and in addition to analyzing whether transactions in the underlying equity or debt securities or loans have been used as the mechanism for violations of Section 9(j) and re-proposed Rule 9j-1, the Commission also would expect to analyze the same activities to determine whether they independently would also constitute violations under the existing antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the securities laws, including Sections 9 and 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, as well as Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, as it relates the market for those underlying equity or debt securities or loans.

D. Preventing Undue Influence Over Chief Compliance Officers; Policies and Procedures Regarding Compliance With Re-Proposed Rule 9j-1, Proposed Rule 10B-1 and Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c)

In addition to proposing rules to prevent fraudulent, manipulative, or deceptive conduct in connection with security-based swaps, the Commission also is proposing a rule aimed at protecting the independence and objectivity of an SBS Entity’s CCO by preventing the personnel of an SBS Entity from taking actions to coerce, mislead, or otherwise interfere with the CCO. Specifically, new Rule 15Fh-4(c) would make it unlawful for any officer, director, supervised person, or employee of an SBS Entity, or any person acting under such person’s direction, to directly or indirectly take any action to coerce, manipulate, mislead, or fraudulently influence the SBS Entity’s CCO in the performance of their duties under the Federal securities laws or the rules and regulations thereunder.

The Commission previously considered whether to adopt a similar requirement when it adopted business conduct standards for SBS Entities in 2016.[98] That rulemaking included, among other things, 17 CFR 240.15Fk-1 (“Rule 15Fk-1”), which requires an Start Printed Page 6665 SBS Entity to designate a CCO and imposes certain duties and responsibilities on that CCO,[99] and Rule 15Fh-4(a), which makes it unlawful for an SBS Entity to: (i) Employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud any special entity or prospective customer who is a special entity; (ii) engage in any transaction, practice, or course of business that operates as a fraud or deceit on any special entity or prospective customer who is a special entity; or (iii) engage in any act, practice, or course of business that is fraudulent, deceptive, or manipulative.[100] In the course of that rulemaking, one commenter requested that the Commission adopt a rule prohibiting attempts by officers, directors, or employees to coerce, mislead, or otherwise interfere with the CCO.[101] The Commission considered that request, but ultimately concluded not to adopt such a rule, explaining that “requiring a majority of the board to approve the compensation and removal of the CCO is appropriate to promote the CCO’s independence and effectiveness. . . .” [102]

Moreover, at the time the Commission declined to include a rule regarding undue influence over the CCO, the Commission had not yet finalized most of the requirements for which the CCO of an SBS Entity would be responsible and had not yet proposed rules relating to trading relationship documentation, dispute resolution, portfolio reconciliation or portfolio compression (“Risk Mitigation Rules”).[103] As the Commission explained when adopting the Risk Mitigation Rules, those rules were designed to further effective risk management by requiring the existence of sound documentation, periodic reconciliation of portfolios, rigorously tested valuation methodologies, and sound collateralization practices.[104] Attempts by officers, directors or employees to hide transactions, submit false valuations or manipulate or fraudulently influence the CCO in the performance of their duties related to the Risk Mitigation Rules would undermine the SBS Entity’s risk management and could pose risk to the market.

In light of the re-proposal of Rule 9j-1 and the proposal of 10B-1 as well as the rules finalized subsequent to the CCO rules, the Commission believes it is appropriate to reconsider the need for a rule expressly prohibiting interference with the performance of a CCO’s duties, even if not directly related to compensation or the threat of removal of the CCO to help ensure the independence and effectiveness of the CCO function.[105] In connection with re-proposed Rule 9j-1 and proposed Rule 10B-1, as well as other rules for which the CCO is responsible, undue influence could arise from many actors (and many actions), and not merely from those actors with the power to set compensation or with hiring and firing authority over the CCO. For example, an employee at an SBS Entity planning an opportunistic strategy could attempt to mislead the CCO by submitting false documentation to the CCO in order to avoid disclosing the build-up of a large position that would require public reporting and thwart the plans of the employee.

Although re-proposed Rule 9j-1 and proposed Rule 10B-1 apply to any person, without exception, and not just SBS Entities, as discussed in the Economic Analysis, the security-based swap market is dominated by dealers. The Commission estimates that dealing activity in security-based swap markets is highly concentrated among a small number of firms who are or will be registered with the Commission as SBS Entities.[106] Because of the concentration of security-based swap activities in a small number of firms that are SBS Entities, their compliance with the Federal securities laws, including those adopted since 2016 and any rules adopted as a result of this proposal, is critically important to fostering integrity in the security-based swap market.

Moreover, existing 17 CFR 240.15Fh-3(h) (“Rule 15Fh-3(h)”) requires an SBS Entity to establish and maintain a system to supervise its business and the activities of its associated persons which must be reasonably designed to prevent violations of the provisions of applicable Federal securities laws and the rules and regulations thereunder.[107] In addition, existing Rule 15Fk-1 requires an SBS Entity to designate a CCO, who must comply with certain duties, including to “[t]ake reasonable steps to ensure that the [SBS Entity] establishes, maintains and reviews written policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with the [Exchange Act] and the rules and regulations thereunder relating to its business as [an SBS Entity].” [108] Failure to establish, maintain, and review written policies and procedures reasonably designed to achieve compliance with the Exchange Act and the rules and regulations thereunder (including re-proposed Rule 9j-1, and proposed rules 10B-1 and 15Fh-4(c) if adopted), may result in violations by the SBS Entity of Rule 15Fh-3(h), as well as Rule 15Fk-1.[109] Proposed Rule 15Fh-4(c) is designed to protect investors and promote the fairness of the markets by supporting the ability of the CCO to meet the CCO’s important obligations to foster compliance without undue influence, which should ultimately support the integrity of SBS Entities and the markets.

E. Request for Comment

The Commission generally requests comments on all aspects of re-proposed Rule 9j-1. In addition, the Commission requests comments on the following specific issues: Start Printed Page 6666

- Do commenters agree or disagree with any particular aspects of re-proposed Rule 9j-1? If so, which ones and why? If commenters disagree with any provision of the re-proposed rule, how should such provision be modified and why?

- As noted in section I.A, the existing antifraud and anti-manipulation provisions of the securities laws, including Sections 9 and 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, as well as Section 17(a) of the Securities Act, already apply to security-based swaps because they fall within the definition of “security” in each of those statutes. Are there particular aspects of security-based swap transactions and the security-based swap markets that the Commission should specifically address? If so, does re-proposed Rule 9j-1 address those areas? If not, what types of fraudulent or manipulative activity, if any, might not be captured by the existing antifraud or anti-manipulation provisions or re-proposed Rule 9j-1, and how might new rules be drafted to address such activity?

- Do commenters agree with the inclusion and scope of the proposed safe harbors in re-proposed Rule 9j-1(f)? Why or why not? Should the actions permitted under the proposed safe harbor be limited solely to circumstances involving actions taken when a person is aware of material nonpublic information? Why or why not? Should the Commission include additional safe harbors in re-proposed Rule 9j-1 to address other types of ordinary course business activities, both in relation to a security-based swap transaction or any reference obligation? If so, how should the Commission define such activities?

- As discussed above, in response to operational concerns raised by commenters on the 2010 proposed rule, the Commission is proposing two limited safe harbors from re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) to address situations when a counterparty to a security-based swap is required to take certain actions while in possession of material non-public information. Should the Commission also create a safe harbor for entering into security-based swap transactions for purposes of hedging some or all of their exposure arising out of lending activities with a reference entity or the syndication of such lending activities? Why or why not? If such a safe harbor is necessary, should “hedging” be defined and if so, how should it be defined? What types of activities should be included and/or excluded in such a safe harbor? What conditions should be included to protect other market participants and to ensure that any such safe harbor is not overly broad? For example, should the safe harbor require that a person using a security-based swap to hedge their interest in a loan while in possession of material nonpublic information provide certain information to their counterparty about the underlying borrower/reference entity? If so, what information should be required to be provided, and why? Should the safe harbor be conditioned on the person using a security-based swap to hedge their interest in a loan being a particular type of financial institution, such as a bank? Why or why not? Should the safe harbor be time limited, for example by requiring that the security-based swap be executed contemporaneously with the execution of the loan or the syndication of the loan? If so, how should such condition be structured? Could a safe harbor for hedging be constructed in a way to always distinguish legitimate hedging activity from other types of transactions? If so, how?

- As previously noted, re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(1) and (2), consistent with Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act, require scienter. In contrast, re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(3) and (4) would not require scienter, consistent with Sections 17(a)(2) and (a)(3) of the Securities Act. Do commenters agree with the proposed standards of care in re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a)? Why or why not? If not, what should be the standard of care for each aspect of re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) and why? Also, should the standard of care be different from the existing provision on which it was based, and if so, how and why? For example, if re-proposed Rules 9j-1(a)(1) and (2) continue to be based on Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a)(1) of the Securities Act, which require scienter, why should the proposed provisions rely on a different standard of care?

• One difference between re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) and the 2010 proposed rule is that the four provisions based on Section 10(b) of the Exchange Act and Rule 10b-5 thereunder, and Section 17(a) of the Securities Act now refer to both actual conduct and attempted conduct. Do commenters agree with the change, as compared to the 2010 proposed rule, to extend those provisions in this manner? Why or why not?

- Do commenters agree with the application of re-proposed Rule 9j-1(a) to actions to exercise or any action related to performance pursuant to any security-based swap including any payments, deliveries, rights, or obligations or alterations of any rights thereunder; or to terminate (other than on its scheduled maturity date) or settle any security-based swap (in addition to, among other things, purchases or sales of, or actions to effect transactions in, security based swaps)? Why or why not?